Simpler Times

These essays are now also available in book form, printed on real paper

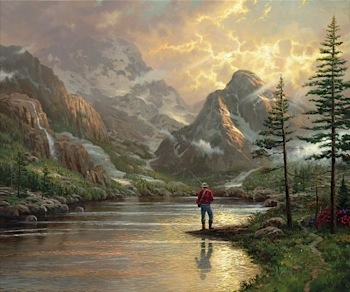

I found an old copy of Thomas Kinkade’s Simpler Times on my daughter’s bookshelf, which I promptly re-claimed for collages. She didn’t mind: neither of us had ever really read it. The book had been sent to me more than a decade ago when I took a writing job for Media Arts Group, the company that sells Kinkade’s pictures. In fact, I poked around on thomaskinkade.com a bit and found the plein-air paintings that I had written about years ago. My words are still there, signed by the Painter of Light himself. You could read my old masterpieces of copywriting if you knew where to look. … I’m not talking.

The book, Simpler Times, and the art that fills it, is all about a return to some kind of good-old-days: stone cottages, warm firelight, cozy villages, and gas-lit streets. This is all elaborated in the book as the opposite of noisy, media-filled, task-list-crazed individualism. Had Kinkade and his co-author written the book today, I assume blog-writing and -reading, and other webby activities wouldn’t qualify as simple-time either. Who would buy a Thomas Kinkade painting of an apartment window glowing with the unearthly fluorescent blue of computer screens? The Painter of Light, 2.0!

Who doesn’t love the idea of old stone buildings lit by fire? Kinkade is popular because his paintings strike some pretty big chords - simplicity is highly attractive to anyone who lives and works in this crazy-complex modern world. Longing is probably not too strong a word to describe the attraction. Also attractive are the various elements that populate these works: stone, water, and fire; cottages, gardens, and gazebos. Here at (low) tech writer, I share this attraction. But all of these elements are brought together in a world as unreal as a model-railroad diorama. What is it exactly? A little too much color in that garden scene? Not quite enough color in that crowd scene? Is it all just a little too much of the wrong idea of perfect? As I flipped through the book (before cutting it up for art), I began to discern one significant way that these pictures go wrong. It’s the water. When I look at the water in a Kinkade painting, I long for a little less simplicity.

Here’s what I see: in Thomas Kinkade’s world, water is harmless.

Take a look at the above painting titled Almost Heaven (you can zoom in on it by clicking the picture to visit the Web site). The waterfalls in this picture sit on top of the earth like they don’t belong there – like they are just passing through: not like they have been carving the surface of the earth for hundreds of thousands of years. One of these uninvited rivers spills over the high-point on a rock jutting out from a cliff, managing a double-miracle: resisting the tendency of water to flow downhill, and also the habit of water to wear stuff down. Other waterfalls in the scene rage with snowmelt, but seem unable to have any effect on the landscape at all. In other works, rivers float through villages on top of the soft earth in perpetual flood, yet also fail to have any erosive effect on the perfect, grassy banks. It seems to me that Kinkade makes a mistake similar to that made by some of the romantic painters of the 19th century: while ‘recording’ what they witnessed in the new territory of the American West, they often mixed up their geology by painting what they imagined, instead of what was. Albert Bierstadt painted the scenery of the Sierra Nevada in California from a mix of memory and imagination. He seems to have occasionally confused and combined u-shaped glaciated valleys with the v-shaped terrain created by liquid water.

At least Bierstadt was never confused about the violence that water can do, in liquid or solid form. Looking at Kinkade’s paintings, we’re left to imagine that God formed the mountains and valleys according to whimsy and then sent the impotent water over it for his own amusement. And, I guess, for painters to have something to paint. Will there be no erosion in heaven?

But if God made the mountains and the valleys, then the shaping of them was done with water. If you’ve ever tried to swim across a river, or escape a rip-tide, or walked under a waterfall, you know that water has power. And power is precisely what is missing from Kinkade’s portrayal of nature.

I can accept the unabashed hopefulness–hope needs nurturing. I can accept the occasional too-sweet sentiment–who doesn’t like sugar in their lemonade? I can almost accept that there is never any strife in Kinkade’s art: after all, he is painting his vision of heaven on earth, and some of us–even before we take in his luminous, idealized landscapes–are invested in the idea that one day our tears will be wiped away and there will be joy. But, while I believe that this kind of heaven is breaking through into the world, I don’t think that it will create the homogeneous and impotent landscape that the Painter of Light portrays. In fact, I’d say Kinkade’s powerless waters (for starters) give his vision itself a dangerous power … power to lure the viewer away from the challenges of reality in the way that psychotropic drugs dilute your desire to find real peace. Take enough Valium and you may just give up thinking about what’s wrong with your life.

One take-away from this kind of art is the idea that the creation is ideally impotent. That in this picture of heaven not only will the lion lay down with the lamb, but the water will never again shape the rock, or otherwise change the landscape. But what Kincade fails to document in his vision is that this shaping and changing is a part of the design. It is part of God’s design that water and earth are locked in constant conflict, and one result of this clash is that the earth is made more beautiful.

Here’s what’s true about water. Water is not impotent. In nature, water moves according to huge and hairy rhythms and gives swimmers and sailors something to worry about. Water tears at the landscape, breaks it down, carries it off, and leaves the earth scarred and changed. Here’s how awesome water is: if Water was invited to make a guest appearance in a game of Rock, Paper, Scissors … it would trump them all, but none would fall more memorably than Rock, which succumbs slowly but utterly to water’s power.

A pretty good example of what can result from all this clash and conflict between water and stone is a little vacation spot in the California mountains called Yosemite Valley. You may have heard of it. There are peaceful places in the Valley, but I’m not sure a feeling of peace is the appropriate response when looking at a waterfall moving 2,500 gallons of water per second and cutting through a two-thousand-foot granite cliff. Water has terrible power and who would want it any other way? But Kinkade’s paintings suggest that something God made powerful will one day ideally lose it’s power, and that is a message with the power to make people mistrust true power, wherever it should be found.

One place where power is seldom trusted, where conflict gets a bad rap, is among the human characters that move here and there on the surface of the planet. While nobody loves the wars that plague humanity, even the proverb says that people shape and change each other, that we are somehow improved by conflict:

“Iron sharpens iron,

so one person sharpens the wits of another.”

(Proverbs 27.17)

Conflict is not evil. It’s only evil when we try to silence or destroy those who challenge or threaten us. That’s what makes war. Allow me to suggest a (low) tech writer people-principle: peace does not come from avoiding conflict or clashes, it comes from accepting these things as part of God’s design for beautiful people.

Or to quote Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., “I would not give a fig for the simplicity this side of complexity, but I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity”.

The photo of Yosemite Falls, 2005, is by Kevin Ingolfsland and is on WikiMedia Commons.