Light From Fire

These essays are now also available in book form, printed on real paper

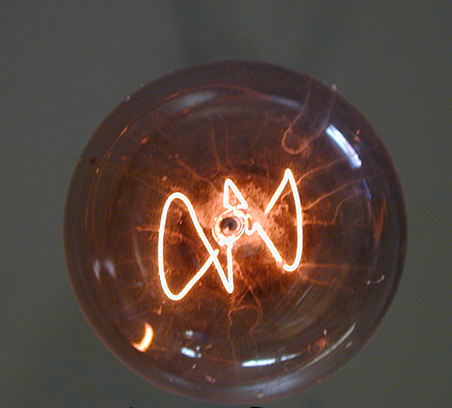

Before it is too late, I’d like to give a little love to the light bulb, old school edition. I’m not talking about the kind filled with toxic gas that glows cold and white when excited by electricity. I’m talking about the real deal: the inefficient, endangered, incandescent, campfire in a bottle. So, a toast: here’s to getting our light from fire. End of an era. … Here’s to the scientists who captured fire in a glass prison, and here’s to Thomas Edison who perfected the technique, enabling the fire to burn without burning out, by robbing it of oxygen. Brilliant madman.

Frequent readers of my blog may wonder why I’m not writing about candles or lanterns, or hey, maybe torches, as beautiful old-timey sources of illumination. I know that a century and a half ago, the light bulb was not a low-tech reminder of simpler times. It was probably a spooky reminder that we were determined to conquer nature, no longer to be subject to the natural rhythms of day and night: the light bulb may have given my low-tech lovin’ ancestors something to fear. Imagine: Edison made a bamboo fiber burn for 1200 hours. Think about that. An inextinguishable flame … a thing that burned for what seemed like forever. Sounds vaguely demonic.

But one of the reasons I write about the things I do, is that our drive to innovate usually involves ditching simple, functional, beautiful tools in favor of hastily designed, indurable, inelegant, ugly things that do very few things only slightly better than the thing they are replacing. Often, when we choose to upgrade to get a single improved feature, we lose an ecosystem of form and function.

Government bodies are beginning to legislate the end of the incandescent bulb (by 2014 in the U.S.) in favor of compact fluorescent lamps (CFL), which last longer and use less power. That’s two good features. They also contain mercury, are a documented danger to low-income workers who manufacture them for export to the U.S. and other western nations, and cannot easily, cheaply, or safely be disposed of (the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recommends that fluorescent bulbs be double-bagged in plastic before disposal, even though two plastic bags won’t stop the leaching of mercury. Nice.) Far more energy is used in the manufacture of CFLs than in the making of incandescents. They are also very expensive, can fade light-sensitive paints and textiles, and have a number of problems depending on the kind of electronics used, related to operating temperature, orientation, and noise. Sure, most of these problems can be solved. But they’ll never make a CFL look like the bulb in the picture above. That makes me sad, and I’m surprised to be sad about it. I’m hearing Joni Mitchell right about now: Don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone?

I was about to call that light bulb a work of art, but that’s silly. It never was meant to be a work of art. But sometimes a simple thing made well approaches a kind of elegant beauty, by chance, or by some inherited creative spark left over in us as a part of the Image of God … occasionally we do beautiful things even when we are simply trying to solve problems, or make life better. Occasionally. I think incandescent light bulbs, with their warm, quiet, clean simple light, are very beautiful. Only not when they are frosted. Frosting is for cupcakes.

An incandescent light bulb hanging in the fire house of the nearby city of Livermore (that’s it up there) has been burning continuously, with only a few very brief interruptions, for almost a million hours, since 1901. It’s got the record, in case you’re wondering. This very bulb (there it is in the picture to the left) burned for every minute of the last thirty years of Thomas Edison’s life, and has been burning ever since. The bulb managed to outlive my grandmother, born the year it was turned on, though my Grandma only just passed away a couple months ago, at the age of 108, and was as bright and clear-eyed as this bulb to the end.

One of the reasons proposed for the Livermore bulb’s long life is that it’s burning at a very low wattage (four watts, which apparently was enough for a fire station night light back when Grandma was young). Low wattage means low heat. Low heat means long life.

So, here’s the deal. Why not just use lower wattage incandescents: let’s split the difference–halfway between 4 and 60 (the most popular wattage in incandescents) makes around 32 watts, still far more than the Livermore firefighters would have dreamed of, and plenty of light for a reading space, if not for a large room. Lower wattage means less power consumed and a longer life. Problem(s) solved. And while we’re at it, I bet most of us could walk around our home or workspace and turn off half the lights and not suffer for it. I wouldn’t even mind a little legislation encouraging me to find creative ways to cut my consumption by half. Why is it necessary to legislate the adoption of an immature, dangerous, toxic, fussy, ugly, and expensive technology? Can someone call the government and ask?

I know, I’m a silly idealist, and it will never work. It’s easier to ask Americans to spend $15 more on a light bulb to solve a problem, than to do less of anything to save $15 and eliminate the problem. I think we feel that we have the right to daylight brightness for 24 hours of the day, and if technology can provide it and boost the economy in the bargain, what’s wrong with that? But it gets tiring answering questions like that.

What I’m really worried about is what will become of lava lamps?