When Printing Left an Impression

These essays are now also available in book form, printed on real paper

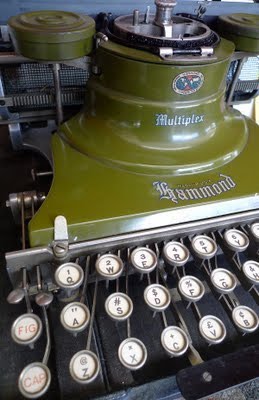

Los Altos Typewriter, local low-tech shrine.

Within walking distance of my house, and central to the region where the personal computer was born and raised, exists a small oasis for those who enjoy old–and lasting–technology: Los Altos Business Machines & Printer Repair, formerly (and more importantly) known as Los Altos Typewriter and Business Machines. In the shop’s original name, “business machines” does not refer generically to coffee makers and copy machines, but to the venerable International Business Machines (IBM), maker of the amazing Selectric typewriter, one of several kinds you can still find at the shop on the corner of State and 2nd in Los Altos.

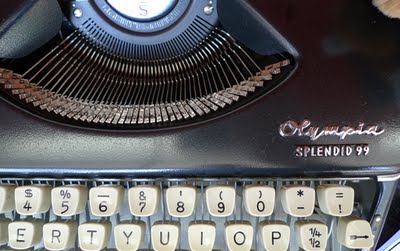

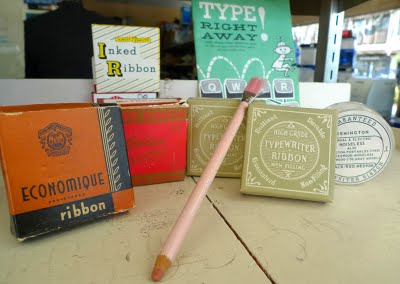

Today, the shop does a lot of printer and copier repair, and for the short time that I was there on a recent visit, several customers came in grunting under the weight of large white plastic office appliances. I was not at all interested in those things, however. I’d come to see the typewriters, many of which are completely functional, and for sale.

Though filled with history, this is no museum. If you’re shopping for a typewriter (aren’t you?) then you’ll have lots to choose from in electric and manual varieties, all with fresh ribbons and ready to type (my masthead–above–was created during my visit). Yet, there are a few interesting models that are just for looking at: the above beauty is pre-World War I, and looks like it might have been designed by someone who went on to design tanks for the war, which is because it was. Click to enlarge this sweet little Trade Mark and read the awesome tag line.

This is a place to get your fix for beautiful mechanical writing machines. This is where you remember why a keystroke is called a keystroke. There is no tap-tap with these machines: here it’s stroke, slap, ka-chunk. Key, plunger, hinge, lever, spring, embossed hammer slapping the ink ribbon against the paper to make an impression. An impression. Say it with me. This is not an image squirted onto paper; this is no mere print, like you get out of the cheap plastic box that shares space under your computer with the dust bunnies and has a lifespan shorter than a hamster. No, not a print, but a press. These machines are one-digit-at-a-time printing presses; all steel, and oil, and ink. Yes.

Let me say a word about computers. Computers are amazing. They contain fascinating mechanisms for taking our input and making things happen. There’s nothing unholy or unnatural about them. As I’m typing these words in a text box in my laptop’s web browser, there are things happening in this computer that are very similar to what occurs when I hit the keys on a typewriter. Only with the computer these things are not happening with oiled-steel levers and hinges, but with electricity. The computer mechanism is just an invisible, electronic version of the physical activity of the typewriter; more flexible, because the electronic mechanism that interprets my effort can be redesigned on the fly by a change in software instructions. But, while flexible, the activity inside the computer is less satisfying because it is hidden from the average user.

What happens inside of computers is at once exciting, powerful, mysterious, intimidating, occult, and slightly de-humanizing. I say de-humanizing because anything that takes the work of creativity, and reduces the mechanism of assembly to an imperceptible and hidden workflow, may lower the bar for entry, but also causes a kind of atrophy with regards to our physical connection to the creative process. With computers, more people can be illustrators, movie makers, musicians, and published authors, which is nothing but good. But these illustrators, movie makers, musicians, and authors will be more removed from the whole body-rhythm of creation as more and more of the mechanism of assembly is reduced to a series of hidden electronic on-off switches that fire a million times a second in a tiny baked chip in a box on your desk. If you turned your monitor off, the only sign that anything had happened would be a slight rise in temperature inside the box. On a cold day (like today) my hands find their way to the left edge of my laptop, underneath which a gray and inscrutable rectangle is processing my keyboard inputs into the very words you are reading right now. It’s warm there.

I’m tempted to say that no one should be allowed to make music on a computer unless or until they have learned to play music by banging, plucking, or blowing on some real-world instrument … but I won’t say it. I will say that if the computer got you interested in music and you are making music now out of loops and samples on a piece of software, that’s not a bad thing. But I can’t stop there: I think you owe it to your body to learn to make music out of nothing, on an unpowered, analog, musical instrument.

I was talking about typewriters. … I have lost whatever skill I had that allowed me to type out a 12-page term paper on Hamlet, as I did in the Bennington College drama department offices circa 1987. I do remember the satisfaction of operating a piece of machinery that sounded like a machine gun (or as near as I’ll ever get). I remember the smell of oil and metal. I remember the way the desk shook under the tremors of the office’s Selectric. But I do not remember how to write a draft –a unique version of a document that you start, and then end, and then edit before moving on to the next draft. Sure, that machine had a backspace corrector that could erase a character at a time, and if you were really patient you could remove a whole line. But once you’d continued on, forget going back and rearranging anything. Your first draft on a typewriter was always only your first draft, and your final draft was your final draft. There was no cut and paste. I mean, technically, you could use some kind of cutting tool, and some kind of paste (remember, kids, paste is not for eating!), but then you’d run the risk that your report would be mistaken for a ransom note.

Today, like all computer users, I am always writing one long soupy draft. Writing on a computer is like making soup: adding ingredients, often in no particular order; taste it, add a little spice, more tasting, let it simmer a while, taste, reduce, salt, and serve. It’s always changing and you won’t do it the same way the next time anyway so it’s no big deal that you can’t remember what you did to make it taste so good. Writing with a typewriter is not this way. Typing is more like making bread; that is to say the process is less forgiving. With bread, you put all the ingredients in and then cook it. If there’s anything wrong (and if you weren’t careful there will be), you make notes on the recipe (“less salt”) and try again. But with soup and computers, it’s much more fluid: there is no first, second, or third draft. Everything on my screen is always changing, and it isn’t locked down until it’s published. And, even then, if I want to publish a modified version of something I’ve written, there’s a button for that.

I am not at all sad that editing is easier today, but I would like to raise a glass to the skill of generations of writers who had to think before they wrote, and had to summon a greater measure of focus before they began to type because mistakes were not so easy to correct. I think of typing on typewriters as a kind of performance. Your thoughts are being recorded as they happen. You have to be on your game. You have to know what you’re doing. With typewriters you couldn’t just spill out your thoughts to be easily and endlessly edited. They pretty much had to come out organized. Can anyone write that way today? More to the point: will we ever learn to be that careful with keyboards again? Maybe if we were forced to think before we write, we wouldn’t be so careless in launching our thoughts into the world like homemade fireworks (there’s a reason why the word ‘flame’ is used to describe hastily-written, offensive emails.)

And I would like to raise a glass to the manufacturers of tools designed to endure decades of pounding; who made their machines beautiful and durable (really durable, not just made to survive a drop, but to be useful for generations); whose machines were not soulless, disposable, software-processing appliances with a 3-year lifespan, but heirloom instruments for creating with words.

And of course, I toast the proprietors of Los Altos Business Machines & Printer Repair, who have chosen to survive in a world hostile to manual tools by servicing flimsy plastic mystery boxes. It can’t be very satisfying to replace plastic parts that were never designed to last, when you are used to cleaning and oiling beautiful steel mechanisms that have been in use for a century. But if doing time in the land of ‘planned obsolescence’ means you’ll be around to fix one more beautiful old writing machine so the next generation can use it, then I approve wholeheartedly.

I’m thinking of bringing my failing printer in for repair (though it would be cheaper to replace it), just so I can waste some wonderful time looking at the typewriters again.